Hey {{ first_name | Neighbor }}. May your text messages from friends be many, your Slack messages from coworkers few, your copays manageable, and your family healthy. May your tax refunds be high and your Amazon cart totals low. May you be happy and healthy and honest with both yourself and others.

For auld lang syne. – AB

➺ Last Call: Like what we do? Become a paying subscriber and help us keep at it for just $3 a month. (Holiday sale ends tomorrow.)

➺ Happy Returns: We’re kicking off 2026 with The Financial Planning Survey, a look at how Oat Milk Elites do/don’t strategize on spending and saving. Participate to receive the results.

PRESENTED BY ➷

Avoid Financial Hubris

Our surveys of high-earners keep finding the same thing: Most professionals are lousy with money. Even people making $250K+ rarely know how their investments are performing or when they’ll be able to retire. Multitasking is hard. Even smart people need help.

Domain Money fixes that. Their CFP® professionals specialize in helping successful people with complicated financial lives get their arms around everything at once:

compensation

spending

investments

taxes

retirement accounts

real estate strategy

Ready to turn that complexity into a single, actionable plan – and a clean dashboard – so you can track real progress without juggling seventeen logins? Book a free 30-minute strategy session and see if it’s time to call in the professionals.

The “FINANCIAL PLANNING SURVEY” is an attempt to understand how members of the Oat Milk Elite engage (or don’t) in short- and long-term financial planning. Full results will be shared with Upper Middle Research members and those that complete the survey.

What we’re drinking about while talking.

STATUS ➽ Ordering a Cosmo

Why do the New York Times’s travel lists matter?

On Sunday, The New York Times released its annual 52 Places to Visit list. An editorial tentpole, the not-as-arbitrary-as-it-seems list is designed to do two things at once: demonstrate the Grey Lady’s cosmopolitan bona fides and reaffirm her relationship with a proudly worldly readership. That dual mandate explains why this year's list includes Big Sur, Hyde Park, and Portland, Oregon as well as Møn, Penang, and Camiguin. Those are not apples-to-apples travel experiences, but the presence of well-trafficked domestic spots allows for a bit of grade inflation.

And, make no mistake, the list is a test. The 52 Places webpage lets readers mark where they’ve been so they can keep score. As an ivory-tower institution, the Times doesn’t want many people scoring higher than the low teens; as a business built on reader affinity, it also can’t afford to have readers going 0-for-52. Thus the love for "Revolutionary America," whatever the hell that means.

TASTE ➽ Après Seriousness

Why is J.Crew selling ski clothes that don’t really ski?

Après Seriousness Why is J.Crew selling ski clothes that don’t really ski? It's not that the StormHood™ head coverage system and RECCO® reflector aids on Arc'teryx's Sabre ski jacket don't work. It's that they kinda miss the point. Towns like Aspen didn't get popular because they attracted serious racers and telemarkers. They got popular because they created spaces in which serious professionals could fuck around – sometimes literally in jacuzzis – without finding out. Aspen, Vail, and Jackson Hole are what Russian theorists call "carnivalesque" environments: places where the rules of decorum that constrain the elite aren’t enforced. Odd as it may sound, that’s why J.Crew just released an aggressively non-technical, 1970s-inspired skiwear collection. The patches and loopy retro fonts don't just give vintage Vuarnet vibes; they give permission to skip the lift lines and party in the lodge. No StormHood™ required.

MONEY ➽ Core Samples

Will Trump turn on his next Fed appointee?

This month, Donald Trump will select a new chair of the Federal Reserve – and, most likely, immediately turn on him in basically the same way he turned on Jerome “JPow” Powell, who he appointed in 2017. The reason for this antagonism can be found in political scientist Richard Bensel’s The Political Economy of American Industrialization, a deliberately dry data-dump that gets a fuckload closer than Hillbilly Elegy to explaining resentment-based politics. Using county-level data from just after the Civil War, Bensel demonstrates that Northeastern financiers exerted control over much of the country in the late 19th century by dictating rates on municipal bonds, mortgages, credit, and railroad freight. Their capriciousness and impunity produced a cross-class solidarity among those outside the Northeast who actually felt the effects of their decisions: farmers, workers, miners, and even Main Street bankers.

Flyover state dwellers don’t learn to resent “capital” in the abstract; they learn to resent bondholders and regulators in New York. It’s a tradition. Trump’s attacks on Powell tapped directly into this geography-coded, quasi-class antagonism – and so will his attacks on his next appointee. Historically speaking, Northeast number-crunchers are to the borrowers west of Pittsburgh more or less as Gargamel is to the Smurfs.

➽ Also… We’ve hit post-peak wine. ➺ Why COSTCO wins. ➺ Should we take the pro-tax rich seriously? ➺ C’mon man, $3-a-month ain’t much.

Want to earn up to $200-an-hour for your insights, get three free months of Upper Middle member-only content, and get a discount on annual membership. Join Upper Middle Research, our professional research platform.

Why resolving to read more fiction may not be such a good idea.

For a hot minute in 1995, coders looked like they might follow in the steps of the Neo-expressionists who taxied north from industrial lofts south of Houston to hang in the halls of power. Hackers, featuring Johnny Lee Miller as Zero Cool and Angelina Jolie as Acid Burn, promised a shadow aristocracy of Galliano-loving Linux fetishists demanding deference if not outright submission. But that’s not what we got.

We got CSV skins, dogshit search engines, backfiring misinformation engines, and Burning Man camps full of palefaces who didn’t know how to handle their drugs. Coders did not produce a culture that commanded mass respect. They did, however, produce a big bad more intimidating than Fisher Stevens on a skateboard – an autocomplete effective enough to take their jobs.

A little over 180 days ago when Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei predicted that AI would “write 90 percent of the code” in six months, Discord servers lit up with furious comments by users with names like “rootkit420” and “TorvaldFucks,” but the usual pearl clutchers didn’t reach for their mollusk secretions. Even as job listings started to disappear and Google, Amazon, and Meta announced mass layoffs, the end of coding as we know it didn’t elicit much of a response from cultural elites or non-tech professionals.

It’s no mystery why. There has always been the sense that coders didn’t belong in the professional class. That they were just a bunch of Palo Alto Hillbillies who struck it rich by living on the right part of the spectrum at the right time. Few said it aloud, but the current semi-silence speaks semi-volumes.

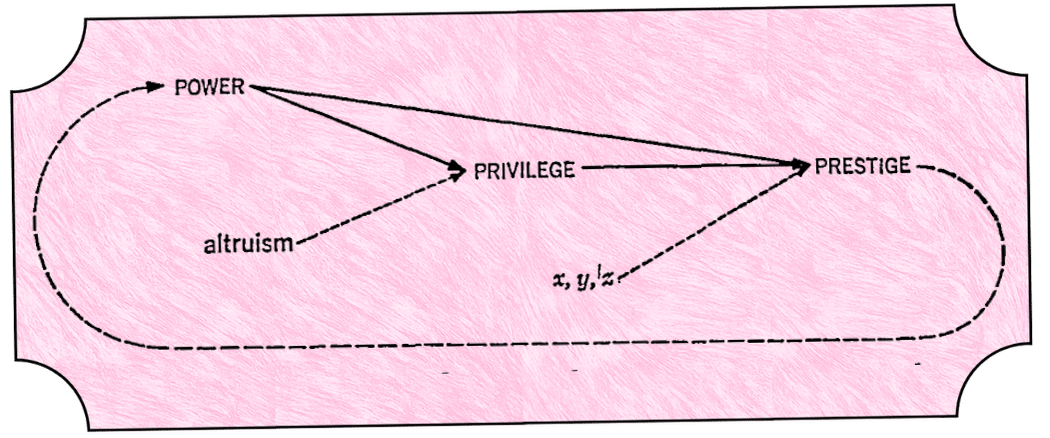

For a long time, coders seemed like they would become, if not a shadow aristocracy, a permanent part of the professional elite. They were in demand – ascendant enough that “maybe I’ll learn to code” became a creative class euphemism for professional capitulation. But most creatives didn’t learn to code. The job didn’t map to their priorities – coders accrued capital without accumulating power or prestige. There were a few reasons for this. The first was that it was fundamentally a skills-based trade. Like carpentry or plumbing, coding focused on less prestigious “object” work rather than more prestigious “people” work. The second was that, unlike professions built around formal certification processes, coding had innumerable on-ramps – everything from elite computer-science programs to state schools to bootcamps to watching YouTube in the basement – and no clear code of ethics. This may explain the lack of concern about the destruction of coding jobs within the professional–managerial class, many of whom see those particular layoffs as unfortunate but not unjust.

Self-described disruptors can’t much complain about being disrupted.

It is uncomfortably, plausible that AI could replace a great deal of coding labor. That's not because coding is not a creative endeavor, but because most coding is not a creative endeavor. Predictive models can generate, refactor, debug, and document – work that is either repetitive or iterative. Over the past two years, jobs listings for “computer programmers” (typically junior, task-oriented roles) have fallen by nearly 30 percent. Listings for “software developers (typically more senior roles involving systems thinking) have declined more modestly. In other words, the ladder is breaking from the bottom.

It’s not as though this was impossible to see coming. In 1966, social theorist Gerhard Lenski wrote that “distributive systems which allocate rewards in ways that cannot be adequately justified are inherently unstable.” In other words, high pay without widely recognized civic utility does not generate the moral authority necessary to command empathy. Put differently, non-coders have no reasons to care more about coders than code. “Prestige is accorded on the basis of social evaluation, not simply on the basis of economic success.”

Coders did not pass their social evaluation.

This failure is obvious not only because of the schadenfreude expressed by members a creative class, which has been destabilized by the diversion of ad dollars toward platforms. Many liberal professionals outside the tech industry view techies as politically suspect, seeing them as ambivalent about labor, regulation, and even democracy. Because of the behavior of handful of tax-avoidant edgelords constantly hurling libertarian-adjacent political kinderzeug, coders are often assumed to lean conservative. In reality, voting patterns in Silicon Valley are no different from those of marketing executives on the Upper West Side. Still, the latter group is suspicious of the former because they never darken the door at Bergdorf’s – and because it’s not entirely clear they’re a group at all.

The British sociologist Frank Parkin had a blunt term for the reason coding professionals never quite managed to become a respectable cohort. “Social closure,” he wrote, “is the attempt by one group to secure advantages by closing off opportunities to another group.” Law and medicine don’t just require skill; they require degrees, years of training, licenses, a narrative of public service, and the polish of people worn smooth by a steady stream of prior vettings. Coding hasn’t built anything comparable. It has shibboleths, sure, but no chokepoints on the way in. No way to keep out talented weirdos.

That openness helped the tech industry hyperscale, creating enormous wealth, but not authority and certainly not moral authority. Sure, tech flirted with effective altruism as a moral justification for monopolistic practices and individual greed, but that ethos was never formalized. Without a clear claim to social value backed by a license, an oath, or a shared ethic of restraint, status remained contestable even with tech firms.

Contestable status is at the core of the decades-long cold war persists between rank-and-file coders and better educated, more socially functional product managers. This conflict was always inevitable. Work organized around people reliably commands more prestige than work organized around things, even when the thing-work is harder, more technical, and better paid. Eliot Freidson, in his classic work on professions, argued that authority and status flow not from technical competence alone but from jurisdiction –from deciding what should be done. Andrew Abbott built on this in The System of Professions, showing that occupations organized around interpreting human needs enjoy greater standing than those defined by mastery of processes.

Coders may have mastery, but, as product-management guru Lenny Rachitsky puts it, a PM’s job is to “identify and solve the most impactful customer problems.” The authority lies upstream, in judgment and prioritization, not execution.

In part because of this, coders tend to seek status primarily within the coder community itself. Languages, stacks, frameworks, LeetCode scores, arcane performance metrics—these create dense internal hierarchies that feel meaningful to those on the inside and opaque to the point of irrelevance to everyone else. The prestige doesn’t travel.

Disrespect does.

The number of CS degrees awarded by trend-chasing American colleges has doubled in the past decade as universities and liberal arts colleges built departments that often felt like trade schools gussied up with copies of Gödel, Escher, Bach. It's certainly not the first instance of administrators chasing the job market – the law degree boom of the 1990s springs to mind – but it may be the most extreme and embarrassing. Colleges went out of their way to train students to work for employers who actively derided undergraduate education as a bad investment.

Recent data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York puts unemployment among new computer-science graduates above six percent – the highest of any major. Jobs aren’t just disappearing because of AI. They are being offshored to Pakistan and the Philippines. They are being modularized, routinized, and quietly converted into contract and gig work. There are some folks with very strong resumes reduced to selling ass their services on UpWork.

It’s not Zero Cool. It’s zero cool. Maybe they’ll learn to plumb.

Enjoying Upper Middle? Please share with your friends. Refer ten new readers and we’ll send you a t-shirt just like hers (and an obscene thank you note). Just use your personal referral link.

Mr. Market is Andrew Feinberg, a retired hedge fund manager who has beaten the S&P 500 for the last 30 years. He is the author/co-author of four books on personal finance.

Dear Mr. Market:

The Wall Street Journal just ran a poll to determine the greatest investor of all time, and they included Jesse Livermore as one of the five nominees. Livermore killed himself in 1940 because he was broke. Am I missing something?

Addled in Altoona

Dear Addled,

The Journal messed up. Livermore is fascinating, but, net-net, he sucks. In 1930, his third attempt to profit from the Crash was a home run and he was worth the equivalent of $2 billion. Four years later, he filed for bankruptcy for the third time. That is insane. When he killed himself, he was $8.3 million in the hole.

To me, Livermore, the one-time “Boy Plunger” of Wall Street, was obviously addicted to gambling. But he was also diligent. Pissing away $2 billion in four years takes dedication.

Livermore is a cautionary tale about early success. People acclaim you as a genius and you believe it. Rewarded for plunging, you plunge even more. Any of you who’ve won big in GameStop, crypto, or Nvidia, take note: Don’t get out over your skis. Remember: No one should have ever to get rich twice.

Then there’s this: Livermore was “at least” the third of Harriet Metz’s five husbands to commit suicide. Not to blame the woman… but try to marry prudently. Don’t become someone’s fifth spouse.

Trust me on this one. I was once someone’s fourth spouse. Bad investment.

Sincerely,

Mr. Market

[1] “One of the very first requirements for a man who is fit to handle pig iron as a regular occupation is that he shall be so stupid and so phlegmatic that he more nearly resembles in his mental make-up the ox than any other type….”

[2] Cross-Golf is a fully democratized version of the sport where you whack and bushwhack in equal measure. Works great in the country and not-so-good in high-density neighborhoods.

[3] Austen is kinky. Her work is about being tied down by social restraints. It has been fetishized by many readers who fancy themselves romantics, but might actually be something else.

[4] Like many other pseudo-bros, my primary parasocial relationship is with Sean Fennessy of The Big Picture podcast. I feel oddly exposed even admitting that because there’s a real intimacy there. He’s spared me quite a few hours of negative self-talk – for better or worse.