PRESENTED BY ➷

It's Not Easy Being Green

So don’t be.

If you own a good watch, you wear it to holiday parties. If you don’t, you see that Cartier Tank flashing by the crudités or that Submariner catching the tree lights and feel… a little naked. Fortunately, the best time of year to wear a watch is also the best time of year to buy one.

Every Holiday Season, the pre-owned watch marketplace Bezel – home to 25,000+ timepieces, all guaranteed free of aftermarket mods and authenticated in-house – features a huge selection of watches marked down upwards of 20% by sellers. That is, by industry standards, massive. It makes Bezel the most joyful, trustworthy way to find the one thing you actually want to wear out.

What we’re drinking about while talking.

➽ Talk Amongst Yourselves

What’s the point of talking behind someone else’s back?

A new study published in Behavioral and Brain Sciences finds that “gossip and verbal punishment are constant” in the world’s most egalitarian societies. In fact, backbiting is institutionalized. Among the BaYaka people of the Republic of Congo, moadjo is a ritual in which elder women comically reenact the behavior of anyone acting egotistically, publicly puncturing their pretensions; among the Kalahari !Kung, “talk” is a community meeting called expressly so people can ridicule, lampoon, and dissect acts of stinginess or aggression. The implication is clear: Your “classy” refusal to gossip is, in fact, an anti-social behavior that enables other anti-social behaviors. Consider it an excuse to fire up the old whisper network at your next holiday party.

➽ Coding in Basic

When is a simple white button-down not a simple white button-down?

Chris Black – the J.Crew vibe consultant and co-host of the podcast “How Long Gone” – is not the first influencer-adjacent figure to launch a label. But Hanover, the preppy “essentials” brand he debuted this week, is unusually because it sells simple stuff: American-made Oxford cloth button-downs, polos, jeans, and semi-graphic tees. The brand isn’t capturing a moment; it's leveraging Black’s “It Boy” persona — he’s a GQ contributor and gadfly — to create a permission structure for opting out of the trend cycle. It's high-status imprimatur, sewed into nicely made American clothes with sub-$300 price points. Weirdly normal. Oddly welcome.

➽ Mitigated Disaster

If we swerve to avoid conflict, what do we wind up hitting?

In the 1990s and 2000s the concern was that adults were overprotective of children. Now the concern should be that adults are overprotective of themselves. Need proof? Look no further than the new app Mitigate, which inserts itself into personal communication with scripts designed to help people “navigate” (read: avoid) conflict. That might sound soothing, but as Upper Middle’s Therapyspeak Status Report found, a majority of people (58%) think therapeutic language muddies conversations, and many (41%) think it does more harm than good. That harm isn’t just personal; it’s cultural. Starting in the 1950s, early therapeutic-culture critics like Christopher Lasch warned that conversations about justice and responsibility were being displaced by conversations about feelings. Lasch argued that choosing the right words in service of being comfortable is worse than choosing comfortable words in service of being right. He’s spinning so fast in his grave right now he’s basically a generator.

➽ Crude Prices

Why are fancy people displaying folksy art?

Heidi Caillier, the interior designer behind Kendall Jenner’s mountain house, made lot of great choices and one choice worth lingering on: She invested in folk art. The AD spread currently being salivated over by throw-pillow patricians doesn’t just show an idiosyncratic carved and painted fish perched on a stack of board games; it shows multiple books on Bill Traylor, the formerly enslaved Alabamian whose drawings now sell for six figures and anchor the outsider-art market. Traylor's posthumous rise parallels the broader surge in interest in folk and outsider art, underscored by record sales and attendance at this year's International Folk Art Market in Santa Fe. Caillier – who regularly sources vernacular pieces from places like Harbinger and Nickey Kehoe – isn’t just being quirky; she’s steering her client toward value.

➽ Also… The year’s best gift book is about taxes. ➺ Jollibee > McDonald’s ➺ A very good auction. ➺ Great restaurants matter. ➺ A compelling case for performative reading. ➺ The dishwasher is cooler than you think.

The “WATCHING WATCHES SURVEY” is an attempt to understand what watches mean and who wears what type. Full results will be shared with Upper Middle Research members and those that complete the survey.

❦ HOW TO BE UPPER-MIDDLE CLASS ❦

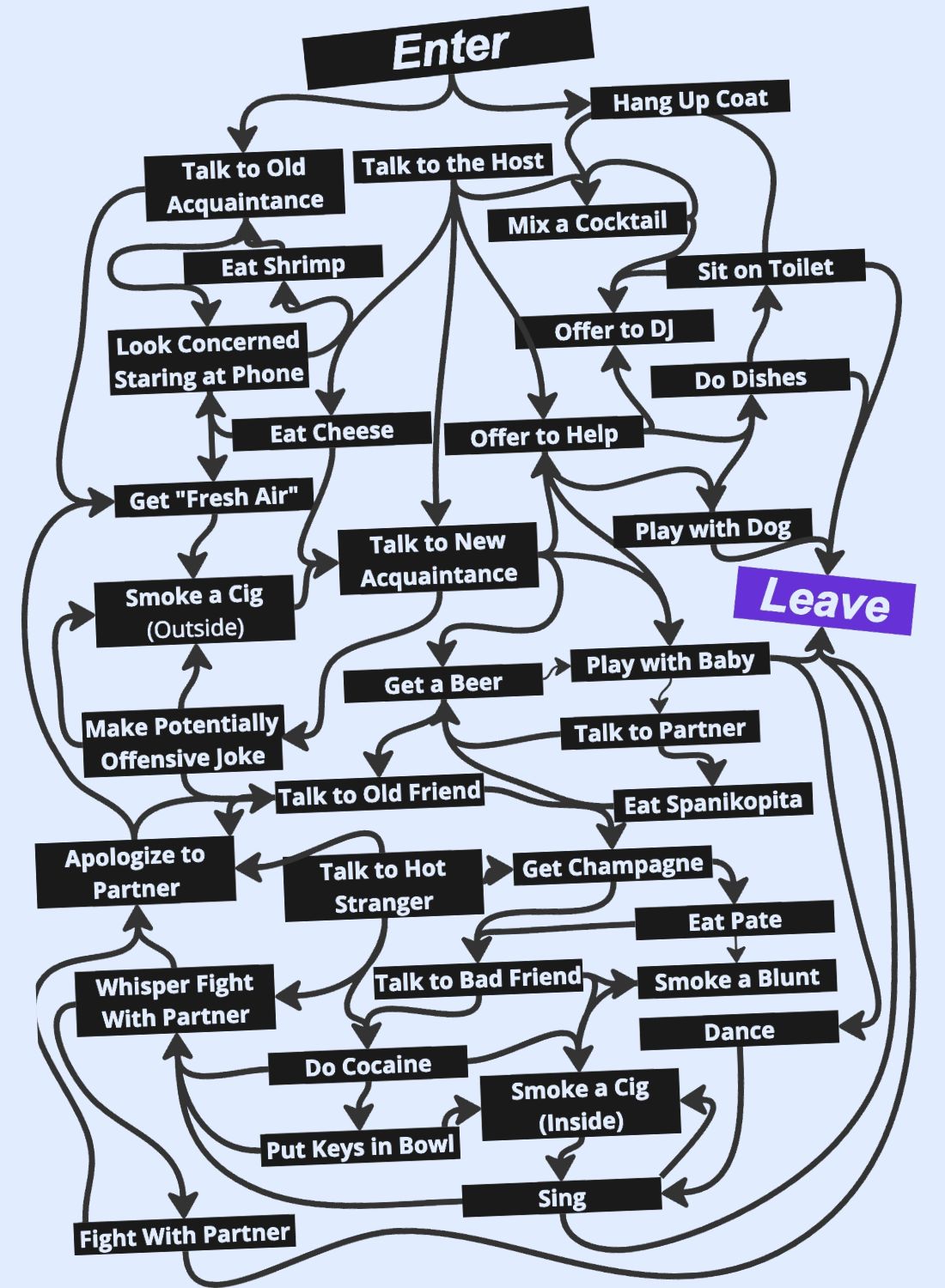

FIGHT (QUIETLY) IN THE CORNER

Every party is a labyrinth and every guest must find their way out alone. This makes parties doubly confounding for dress code followers trained to anticipate and optimize. That works in situations with a few variables, but not hundreds – which is why otherwise semi-happy couples inevitably wind up hissing in the corner. Neither supportive partner stuck to the plan. How could they? There are too many choices. Shrimp is a trust fall. A new acquaintance is a side quest. Cheese is a tactical retreat. A hot stranger is entrapment. Spanakopita a last ditch effort to counter the Krug. Even when the host gets the lighting right (rare but critical), it’s hard not to get in and out without also getting into other kinds of trouble.

CLASS NOTES ❧ Dept. of Public Relations

Why The New Yorker works for the people who hate it.

Wherever he is – hopefully, for his sake, in the arms of a Baltimorean bear – John Waters has probably not watched The New Yorker at 100, the credulous, Judd Apatow–produced centennial documentary that dropped on Netflix last Friday. But if by some chance he has, he likely flashed his pearly yellows seeing his old, shitstained barnyard tricks performed by a stable of show ponies.

In 1973, Variety critic A.D. Murphy condemned Waters’s midnight flick Pink Flamingos as “one of the most vile, stupid, and repulsive films ever made.” Waters – who understood disgusting the squares was the best way to reach swervy hipsters queering lower Manhattan – was so thrilled he plastered the insult on posters. It kept them in line with the trailer, which didn’t show a frame of the movie – not the anal lip-sync, not the fecal denouement – and instead led with a decontextualized quote from New York critic Robert Osborne calling the film “riotously sick.”

In truth, Osborne rather admired Waters. But the Pope of Puke didn’t want that getting around. Disgust was the brand. Revulsion was reputation.

Just as Waters burnished his legend by amplifying the derision of people he never had any interest in reaching, the staff of The New Yorker spends the new documentary enthusiastically self-polishing their mythos1 by echoing the critiques of their populist detractors: The magazine is too sophisticated, too hard to read, and too literary. The film is more focused on out-group derision than in-group appeal because that’s the more potent force.

The New Yorker at 100 is ultimately less about the magazine itself than about the rise and rise of symbolic elitism: prestige generated by appalling an out-group rather than challenging an in-group. Unfortunately, that makes the film timely. Real elite culture –work that demands too much of its consumers to reach a mass market – is increasingly hard to find, whereas symbolic-elite culture is everywhere from A24 to Soho House to NPR to TED to, yes, The New Yorker. Fueled by the very populism it purport to oppose, symbolic elitism functions as a cultural reallocation mechanism, starving genuinely elite work. Difficult, uncommercial, serious art – the kind of work that once required demanded by elites – gets pushed out by institutions that perform elitism in far more accessible ways.

Performing elitism is much easier than doing elitism because the audience is bigger. Also, dumber. The audience for elitism is elites. The audience for performed elitism is populists looking to cudgel people who read into submission. As Jan-Werner Müller argues in What Is Populism?, populists always believe in a “corrupt elite”2– that vaguely cosmopolitan blob – and a “proper elite,” made up of the wealthy, powerful men whose moral authority stems from their ongoing communion with “real people.” The New Yorker is, and always has been, the house organ of the corrupt elite. And it zealously guards that market position.

In the documentary, Andrew Marantz, the magazine’s chief crank correspondent, describes being told by Trump rally-goers: “All you elitist motherfuckers don’t understand the first thing about this country.” Then he describes filing the quote only to see a typographical accent placed gently over the first “e.”

“I think we’ve proved their case,” he deadpans.

He’s right. And it’s no accident. The élitist motherfuckers want to prove the populist case against them because their aura dims without resentment. The magazine’s detractors are the people most convinced The New Yorker represents the corrupt elite and, oddly enough, actual members of that corrupt elite seem willing to take their word for it.

This dynamic isn’t limited to glossy journalism. Symbolic-elite products flourish across cultural sectors. TED was built on the neoliberal fantasy that ideas can be democratized without being denatured. Soho House markets creative-class exclusivity while admitting “partnership managers.”

Often, symbolic behaviors provide air cover for more direct forms of cultural quasi-treason. Consider the Met Gala. The first Monday in May is defiantly elite. It’s the whole donor class dressed in spaceship upholstery. But the Costume Institute’s blockbuster exhibits in the museum aren’t elite at all. They bring in crowds that wouldn’t know a Rubens from a reuben. That’s very much the point. The execs at Condé Nast, which runs both the Gala and The New Yorker, are really good at misdirection.

In 1999, The New Yorker launched the New Yorker Festival, which rapidly became the city’s flagship “high-culture” event. That was bad news for the Lincoln Center Festival, which had been operating since 1996 and shut down in 2017. The Lincoln Center Festival consisted of Beckett cycles, Bolshoi residencies, kabuki performances, contemporary-music marathons, and avant-garde international productions. The last New Yorker Festival featured Jon Stewart, Sarah Jessica Parker, Christopher Guest, St. Vincent, Emma Thompson, and Ken Jennings. It is, to borrow the Netflix exec’s too-quoted phrase, a gourmet hamburger.

The in-group knock is that it’s all a bit dull, but the out-group criticism – that it’s too sophisticated – subsidizes the Festival’s credibility. Doubly so now that the out-group is in power. This year’s Kennedy Center Honors went to George Strait and K.I.S.S. That probably augurs well for festival attendance.

The most revealing moment in The New Yorker at 100 comes late in the film, when Editor-in-Chief David Remnick says of the magazine’s mission: “It is a movement. It is a cause for high things. If that sounds sanctimonious, I do not care.” The statement is performative, but also sincere. Two things can be true. Remnick can be both a generational talent (he is) and a very savvy, slightly cynical brand manager.3

He’s definitely savvy. The New Yorker boasts more than 1.3 million subscribers—some of whom even read the magazine. At the same time, The Paris Review is in semi-permanent restructuring, Harper’s is fighting for solvency, Tin House has abandoned print, and Guernica is, rather fittingly, a smoking ruin.

In 2023, when John Waters spoke to The New Yorker’s Michael Schulman about the Academy Museum retrospective and his new Walk of Fame star, the king of trash explained his strategic transgressions with typical clarity. “You embrace and make fun of what they use against you.” Then he laughed and said he’d become “so respectable I could puke.” The man who once thrived on bad reviews was queasy getting good ones.

Ultimately, The New Yorker at 1004 is little more than a good review of a good magazine. Nothing to puke about. But that’s precisely the problem. The only people who will feel truly strongly about the film will be the people who don’t watch it. In a very real sense, it was made for them.

[1] There is literally a part of the documentary in which the cartoon editor whines about how hard her job is because she has to look at a lot of cartoons. It seems like maybe she’s become one.

[2] This would have been a slightly more punk rock name for this newsletter.

[3] I bumped into him (physically) in an elevator at Conde one time and told people about it for weeks. Huge admirer. The point isn’ that Remnick is unworthy in any way. The point is that the institution isn’t precisely what it purports to be. Never was, TBH. It started as ad sales-focused humor rag.

[4] It’s not worth dwelling on, but isn’t that kind of a weird name for a movie? An editor should have cleaned that up.