A senior vice president of operations walks into an antique store.

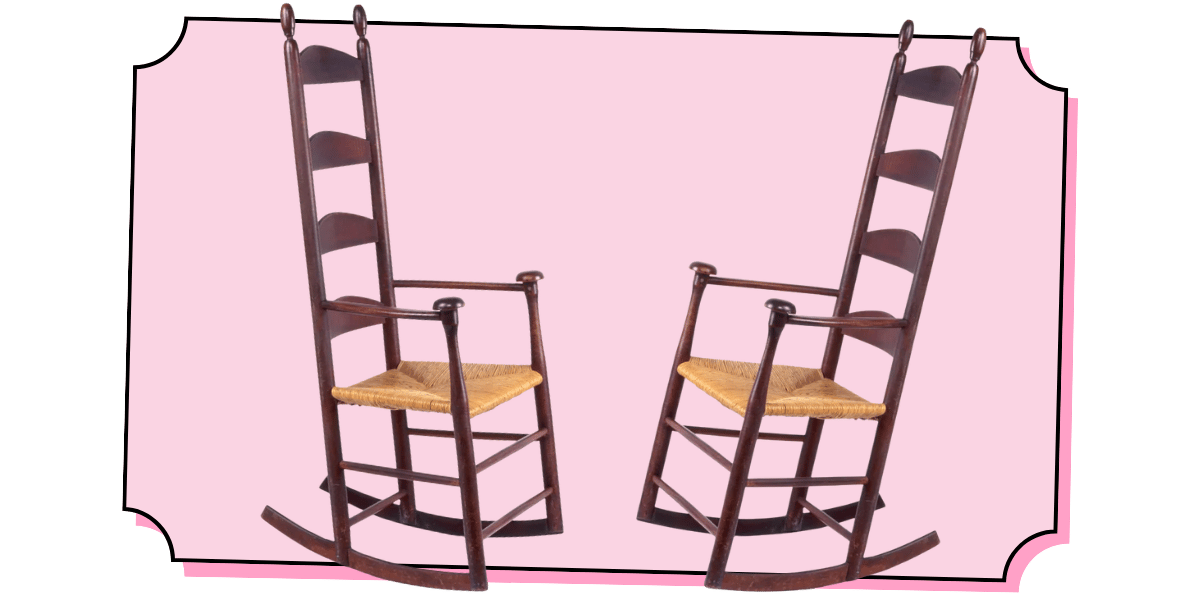

She has time before dinner and no intention of buying anything. The store has the skunk weed smell of wood polish. She pokes a Chesterfield sofa and fondles a bored-looking ceramic spaniel. Then she spots a ladder back chair next to a tole side table. It’s tall with a woven rush seat and has been given pride of place. She reads the tag hanging off the side: “Enfield Shaker Chair Circa 1830. $1,800 $1,450.” The price seems obscene2, but the chair is special. She’s longed sensed a person can only prioritize making one thing at a time – a product or a profit. She imagines the man who made the chair – some humble bearded ascetic – chose the former.

She doesn’t buy it because it will match her Danish modern coffee table or her Noguchi lamp or the Eames lounger her husband bought six months prior as an “investment.” And she certainly doesn’t buy it because she needs it.

She buys it because, when she sits in it, she feels a specific kind of relief. The great project of her professional life is reducing roles to ever smaller, more measurable tasks and responsibilities. She creates complexity in service of savings. Naturally, she craves simplicity. But she can’t afford to be simple; she can only afford simple things. She buys the chair because she’s jealous of it. It’s imbued with a feeling she doesn’t have.

It’s fulfillment. The chair is not the product – much less creator – of a workflow so splintered that participants cannot derive meaning from their work much less imbue the object of their work with meaning. The chair has quintessence, an it-ness derived by from the fulfillment of its makers. On some level she knows this, though she’s good enough at rationalizing her work to hide her moral injury from herself.

She brings the chair back to her apartment, pulls it up to her IKEA desk3. She googles the Enfield Shakers and is surprised to learn that no one artisan built the chair – that the Shakers ran what was, at least by the standards of their time, a massive manufacturing business: furniture, seeds, brooms, herbs. They divided labor. Posts were turned in batches. Slats were cut separately. Seats were woven in a special room built for that purpose. She wonders who handled their ops.

Lots of people. She finds out the Enfield Shakers created an ops org consisting of “trustees” and “deacons” who handled the “temporal affairs” of the community while true authority remained with a small, charismatic ministry that derived legitimacy not from efficiency but belief. Management was custodial rather than extractive, bounded by doctrine and accountable to a moral vision. Initially, complexity was only allowed to the degree it did not interfere with purpose, making the work feel empty or cruel. Profit was less an orientation than a byproduct of the “Hands to work, hearts to God” religion doctrine.

She toggles between the article and LinkedIn. A former colleague has posted about “operational excellence in a tightening market.” She clicks back. She reads a quote from an Enfield Shaker eldress: “In any community fitly joined together there must be many who are inconspicuous, but who [provide] for the solid substance without which the wholesome community could not exist. To be a person of that sort is worthy of one’s ambition.”

She leans back a bit, using Siri to transcribe the quote into her journaling app. The chair creaks, but doesn’t give. It feels as though she is being given permission to produce simplicity in response to the complexity of the world. It’s a nice feeling, but not a new feeling. Years earlier, when interest rates were near zero, she worked at a software startup where more time and focus went toward refining the product than profiting from it. It was SaaS, sure, but those years were some of her best. She produced simplicity and consumed complexity – largely in the form of second dates.

The startup failed. Rates changed. Ce’st la vie. There was more money in management, and abstraction so she leaned into documentation and goal setting: OKRs, RACI docs, KPIs. She got a job and then a promotion and then an office with a door. She went in eyes open. She’s read her Barbara Ehrenreich – “through a careful analysis of the production process, the complex and intellectually demanding work of the craftsman could be broken down into simple, repetitive motions to be divided among less-skilled workers” – but she also has to pay rent.

She keeps reading and learns that as the number of trustees and deacons among the Shakers grew, the community shrank. It’s strikes her that workers – congregants, really – didn’t leave because of money. They weren’t there for the money. They left because they no longer felt fulfilled. When supervision replaced shared belief the system began to fail.

She wonders what her coworkers would do if they weren’t in it for the money, if her company was a spiritual project. She concludes, uncomfortably, that they would either force her out or leave themselves – that her work would become a barrier to their fulfillment. Then she reads that many of the deacons left before the rank and file, not wanting to undermine a project that had deep meaning to them.

She sympathizes. Her work has meaning to her. Deep meaning. Of course it does. There’s just a distance between meaning and fulfillment. That distance is measurable in the time she spends at retreats and in therapy and, sure, shopping. It’s measurable in how much a producer of complexity will pay for simplicity – a bit of relief, a few pieces of polished wood.