Hey {{ first_name | Neighbor }}. The temperature is hovering around 0°F where I live today, but the real feel is in the teens. I like the idea of real feel. It suggests that one data point is not, in and of itself, enough to describe the experience of being outside.

There’s a real feel for everything. Love. Income. Democracy. All of it. – AB

➺ Sexy Stuff: If you haven’t already, take our “LUSTFUL YEARNING SURVEY.” Early data indicate that y’all get down. Good. Respondents – and members – get results.

➺ Passing Thought: My jeans were distressed when I wasn’t. I guess I changed.

What we’re drinking about while talking.

STATUS ➽ Dolby Theatrics

Why do entertainment reporters use that word?

Snub is an odd word. Borderline onomatopoetic, the verb – etymologically rooted in the Old Norse snubba, meaning to cut short or nip – has become seasonal. Come late January, entertainment reporters revive it to describe what has befallen the producers and actors denied Oscar noms, which is to say… losers. This year, Ariana Leo got snubbed (according to The New York Times), Paul Mescal got snubbed (according to Variety), and Wicked got snubbed (according to someone drinking on the job at Deadline). By choosing their word carefully, these outlets quietly cast the Academy as a capricious social arbiter – a slightly drunk dowager whimsically dispensing favors and slights. Though that’s not entirely inaccurate, it’s an odd accusation, since capricious social arbitration is the literal point of a popularity contest like the Oscars. “Snub” implies that the Academy somehow owes Mescal or Grande recognition simply because they did a thing. It doesn’t – and that’s not how life works (at least outside Hollywood).

TASTE ➽ The Lonely Island

Why is Rachel McAdams snarling like that?

Robinson Crusoe lives in the popular imagination as a book about a castaway. It’s really not that. In the novel, Crusoe is constantly encountering pirates, captives, and cannibals. He’s not alone; he’s unencumbered by social structures. The island isn’t a restraint; it’s permission to ruthlessly and directly pursue his self-interest. Director Sam Raimi, whose Dumpuary flick Send Help drops a resentful white-collar underling on a tropical island with her scumbag boss, gets this. Like Defoe, he’s less interested in coconuts than in what happens when smart people are given permission to go coconuts on each other. He understands that “resourcefulness” is a euphemism for who would survive in the wild.

Send Help borrows liberally from other contested-island flicks – Lord of the Flies, The Most Dangerous Game, The Beach, and even Battle Royale – but its real source material is the shockingly Crusoe-inspired Survivor. Linda Liddle, played toothily by Rachel McAdams1, turns out to be a big fan of the show (realistic given that Survivor’s youngish, high-income audience is what’s kept it on CBS for more than four decades). As soon as she hits the beach, she understands the game and starts playing to win. This makes her terrifying and also, more tellingly, very happy.

MONEY ➽ Collective Irresponsibility

Why is “smart” investing getting dumber and more dangerous?

New research from the money manager and researcher Hari Krishnan illustrates the surprising degree to which a bunch of very responsible professionals with 401Ks and Vanguard Fund exposure could destabilize the stock market – particularly if investment stops or slows due to an economic downturn. Krishnan’s model shows that as passive investing increases, fewer investors are engaged in active price discovery – which causes prices to lag underlying reality and then adjust through sharper, more volatile corrections. When the effective share of passive investments exceeds 83%, the possibility of markets flatlining becomes non-zero. Obviously, that won't happen, but the model illustrates the potential fragility of the the stock exchange given that the current share of passive investments is somewhere north of 50%. So, yeah, your advisor told you that "buying the market" is good and stockpicking is bad, but... someone has to do it.

➽ Also… Whelp, the R-word is back. That’s bigger for Boston than the Super Bowl. ➺ There’s no shame in CBS schadenfreude. ➺ The gas mask of the season is the 3M pink and green. ➺ Please take a moment and help me not get a job.

The “LUSTFUL YEARNING SURVEY” is an attempt to understand what’s attractive to members of the Oat Milk Elite and what we’re willing to do about it. Full results will be shared with members and those that complete the survey.

The national media continues to call the occupation of Minneapolis by ICE an immigration crackdown. But numbers and eyewitnesses suggest otherwise. Deportations are barely up under Trump. What’s up is performative, Instagram-optimized cruelty, which members of the professional managerial class now witness while commuting to their jobs at Target, 3M, General Mills, and Best Buy – or even just dropping the kids off at daycare.

To understand what it feels like inside and outside the state’s wealthier enclaves – where many assumed they would be insulated from state violence – Upper Middle reached out to local readers2. Here’s what they had to say:

“We see ICE everywhere all the time. My neighbors and community members (including daycare and school teachers) are being taken. Everyone who is brown – including fully legal citizens – are walking around with targets on their backs and are afraid to live their lives. Close friends were eyewitnesses to the murders. The trauma is widespread and varied, but people are only doing more to show up and stand up against the occupation…. I've never been more proud to be from and live here.” - Minneapolis

“My twin sister is an executive director for a non profit that is serves low income people. ICE came asking for I-9s and when she said they needed a warrant, they said they’d come back. One night later we were followed by three trucks.” - No Location Shared

“We are being made to be an example of because of what we offer our residents (ex: paid leave, social services, education, etc.) They want to show how these are failed policies, but they aren’t…. What has happened to our moral character as a nation? Regardless of your political views, we need to be able to say it is wrong when it's wrong. And it is wrong. They are not ‘going after criminals.' They are arresting, detaining, and DISAPPEARING legal residents…. I have a couple employees that are staying home from work because they feel unsafe driving to work. They have legal status here.” - Minnetonka

“I keep my head on a swivel whenever I'm out. My BFF, who's a social worker for hospice patients, has seen ICE harassing them in their homes. I'm in a volunteer group chat focused on bringing kids to school and making sure they don't go hungry. I just want to be normal, but I can’t.” - No Location Shared

Neighbors are missing from work, children are missing from school, people are tense and scared. We see [ICE] everywhere…. Children [hear] about "the kidnappers" and the "green gas" from their peers. - North Minneapolis

“I am terrified of what our community and our country will look like moving forward. This is no longer an immigration issue, this is an assault on our civil liberties. Observers and protesters are capturing everything on camera, yet our government not only kills peaceful observers but then lies about it.” - No Location Shared

Don’t retreat into econospeak.

In his new book Elites and Democracy, political theorist Hugo Drochon3 reanimates the pessimists. Vilfredo Pareto. Gaetano Mosca. Robert Michels. These are names all but redacted from American textbooks – the names of men who refused to grant the premise that democracy is the rule of the people.

In his extremely bracing (but shockingly digestible) book, Drochon revives Pareto’s “circulation of elites,” the idea elites change, but elite rule doesn’t, Mosca’s “ruling class,” the idea rule inevitably becomes hereditary, and Robert Michels’s “iron law of oligarchy,” the idea that democratic orgs can’t help but concentrate power in the hands of the few. By describing democracy as a form perpetual minority rule, Drochon does not seek to undermine the political project, but to explain the stormy present – the rise of populism and the political fracturing of the West – and present an alternative viewpoint on the whole messy thing.

Upper Middle spoke to Drochon about what it means to be elite and what it means to be a fox when lions rule. (Elites and Democracy is available now on Amazon.)

What first drew you to the work of Gaetano Mosca, Vilfredo Pareto, and Robert Michels – a group of theorists – often described as pessimists – who seek to redefine democracy as a rule of elites.

A lot of us view democracy as the sovereignty of the people or majority rule, but reality challenges that view. Engaging with these scholars, who were better known a few generations ago, can definitely feel like a cold shower because they’re skeptical of the idea political elites represent the masses. But if you introduce their ideas to educated people, there is almost instant understanding.

A lot of people – and a lot of political theorists in particular – have spent the last decade trying to make sense of the moment that gave us Trump in the U.S., Brexit in the U.K., and Marine Le Pen in France. It was a populist moment, but the populists were all elites themselves. I think it drove home this old idea that democracy is a form of rule by elites endlessly contested by other elites. Sometimes you need cold shower thinking to get clean.

Most people reading this are used to hearing the word “elite” used in the context of a pejorative like “coastal elite” or “ivory tower elite” or worse. How do political theorists like yourself use the term?

The term elite is coined by Vilfredo Pareto, in 1902. He’s half French, half Italian and he’s lecturing in Switzerland and he doesn’t want to talk about aristocracy or class in a Marxist sense. He doesn’t think that if there’s a proletarian revolution, class will disappear. He thinks there will simply be a new class of rulers, a political elite.

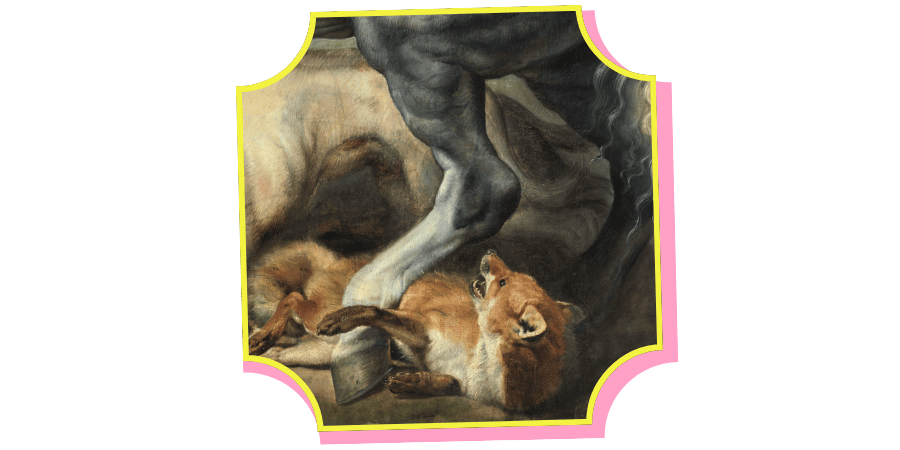

Pareto wrote about foxes and lions. Why do elites and political elites tend to fall into these types in the first place – and why does that distinction matter now

Borrowing from Machiavelli, who talks about the ideal ruler as a combination of a fox, which is smart enough to avoid traps, and a lion, which is big enough to scare away wolves, Pareto says there’s no ideal prince because monarchy is bad, but there are two types of elites. Foxes rule with what Italians call combinazione. They’re decentralized. They’re skeptical. They’re slow to use force. They’re a bit corrupt. The lions rule by force and centralization. For most of our lives, foxes have dominated. Now we have lions.

This cuts beyond the classic left-right divide. The establishment of parties tends to be more fox-like on both sides. But we’ve seen their power decline because they don’t use force. As Pareto put it, they “give in to humanitarianism.”

It seems like foxes dominated American politics for almost a century –really since FDR. Did that long run create a kind of political naïveté, especially when it came to recognizing lions?

The postwar consensus held for such a long time, one fox-like group of elites came to believe that they could always dominate, which is, of course, sort of tyrannical in its own way. As Mosca wrote, you don’t want one social force to dominate. The measure of civilization is how many different social forces can be harmonized and brought together into a whole. And perhaps that’s something that’s been lost: There’s been no entry point for new social forces to be able to express themselves. A lot of people seemed to think Obama represented a new social force, but it didn’t really turn out that way.4

Is it fair to say that fox-like elites often mistake dominance—or moral authority—for legitimacy, and underestimate how much unresolved pressure is building beneath them?

Sometimes there’s a disjunction between the sentiment that dominates the ruling class and the sentiment that dominates the ruled class. Normally, the way this is dealt with is that some people from the ruled class are integrated into the ruling elite. That’s elite circulation. But if that divide becomes too large for too long, then you get some form of revolt. Pareto talks about this in a very simple way. He says: you have A, the established elite; B, the rising elite that challenges A; and C, the people. B says to C: “We will change things. We will give you more power.” Of course, that never happens, and C always remains the people.

The important point is that if A believes that its way of ruling is simply normal – if it mistakes its own values for legitimacy – then it loses sight of the fact that other sentiments exist and are accumulating force.

If group C is never in power, what exactly is the point of democracy? How is it a legitimate form of government?

If you accept that elites rule, you can’t think of democracy as the sovereignty of the people. You have to come at it from a different angle. I’ve coined – that sounds pretentious, but anyway – a term: dynamic democracy. I think we should consider democracy the attempt to achieve the unachievable goal of total participation. It’s maybe less of a system than an orientation.4

The first Trump administration seemed like circulation. The second seems more like a revolt.

Absolutely. The so-called “adults in the room” during the first administration were political elites. They’re gone. The current administration is largely fox-less.

It seems like Trump has been destabilizing for foxes in part because so many of us live in environments populated entirely by other foxes. Specifically, I’m talking about corporate environments, where fox-like thinking has been rewarded. How has that shaped the American elite?

Bureaucratization produces a kind of emasculation – a term used by the American sociologist C. Wright Mills in his book White Collar – where people are no longer owners but managers. At one point, convenience store owners ran convenience stores. Now managers do. And similar patterns of nationalization and scale occur all over. This creates a class of people who appear elite – educated, salaried, respectable – but who lack real power. These people are foxes by profession. They’re trained to negotiate, to manage, to communicate, to administer – but they don’t command. And if Pareto is right, then history is circulation. Sometimes you’re in, sometimes you’re out.

Foxes had a very good run.

So for the foxes reading this—professional, managerial elites who feel politically sidelined—what, concretely, is a fox to do?

If you’re a fox in America or in Britain, you’re up against it. What can we do? I would say: Look at the energies that seem to be pushing against Trump and help pull them into institutionalized politics. Look at who is successfully organizing in Minnesota, who is appealing to energetic non-elites. Start there.

At one point in the book, you reference Aesop. Why did you feel the need to return to ancient wisdom here?

Michels referenced Aesop in his work, specifically the fable of a dying peasant. On his deathbed, the peasant tells his sons that there is a buried treasure in the field. So, after he dies, they get very excited, and they go out and dig up the land to try to find this treasure. Of course, there is no actual treasure. But by digging up the land – tilling it – they make it richer and therefore become richer themselves.

Digging for things, including true democracy, that don’t exist may sound like a waste of time, but the effort produces good outcomes. It’s funny how ancient wisdom comes back to help us to think things through.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

[1] In retrospect, one of the reasons Mean Girls is a five-star classic is that Rachel McAdams is so obviously cool that even people watching the movie wanted her approval. I still do.

[2] Thank you to many of you who took the time to respond. I’m thinking of you and your families and of a long afternoon I once spent wandering down the street in Northfield with a hot coffee and thinking about living there. Minnesota is a fucking treasure.

[3] Hugo is half French and half Irish and teaches political theory in England. That’s what we like to call a hilarious predicament.

[4] Maybe bailing out all the banks and ensuring financializers behaved with total impunity was not, in fact, a great idea. Boy, IDK!