Hey {{ first_name | Neighbor }}. When I was twelve, my parents let me take out our old Boston Whaler by myself. I did so often enough I wound up in the good graces of a pod of harbor porpoise, who’d circle the boat. It thrilled me that life could be like that.

When I feel down, I sometimes wonder if it’s stress or just a lack of porpoise. – AB

What we’re drinking about while talking.

STATUS ➽ Elite Perversions

Why does this kid want to sit alone?

In a provocatively titled new piece for The Times1 – “Nearly 40% of Stanford undergraduates claim they’re disabled. I’m one of them” – junior Elsa Johnson skewers a system that accommodates dubious conditions (night terrors, gluten intolerance) and ends up, as she puts it, “punishing the honest.”1 What makes the essay interesting, though, isn’t the silly programs. It’s that Johnson is one of the “savvy optimizers” she describes rationally responding to a perverse incentives.

Consider this: You're a Stanford student looking to convert status into optionality. What do you do? You join the Stanford Review, a conservative pub founded by Peter Thiel and historically run by his acolytes, bash your alma mater in public, and cultivate a pariah status so you can secure a media gig (or VC sinecure) by claiming a political disability. It’s rational, perverse, and pretty damn obvious.

TASTE ➽ Geckos All the Way Down

What is Jason Alexander doing here?

Super Bowl ads are cheap. Or rather, they’re cheap relative to the marketing budgets of the companies that buy them, all of which sell commodified, mass-market (or mass-mandatory) products: GLP-1s (Ro), insurance (GEICO), beer (Budweiser), soda (Coca-Cola). As chronic poster and Ro CEO Zachariah Reitano explained this week, the Super Bowl bet has capped downside – a low single-digit percentage of annual marketing spend – and uncapped upside. Before the Gecko, GEICO was the eighth-largest auto insurer in America. After, it was number two.

The Gecko didn’t work because it differentiated GEICO’s product. It worked because familiarity shaved a few percentage points off customer acquisition costs, boosting the efficiency of every subsequent media buy. That’s why luxury brands – save Cadillac, which is introducing an F1 team – are absent from this year’s broadcast, and why the celebrities skew… old and edgeless2. Cool sells, sure, but the big money is in familiarity.

MONEY ➽ Domex

Why isn’t the dollar worth a dollar?

The dollar is down about 10% against the euro since early 2025, prompting not-so-hushed whisperings among currency traders and tourists paying the bill at Café de Flore in the Paris 6th. But the dollar isn’t just down abroad; as economist Matt Stoller argues, it’s also down two towns over. In a recent Substack post, Stoller suggests that spending inequality is now rising faster than income inequality, creating the conditions for what he calls a “boomcession.”

In practice, this means that while real wages grew by roughly the same amount in 2018 and 2025, the gains in 2025 were absorbed by non-optional costs – housing, health care, utilities, and financial fees – rather than discretionary spending. Wealthier Americans are shielded by choice and better rates, making their dollars effectively worth more. This isn’t new – between 2006 and 2020, poorer metro areas saw 8.8% higher food inflation than wealthier ones – but it’s intensifying. When people talk about a K-shaped economy, they’re not just describing who has dollars, but which kind of dollars they have.

➽ Also… Wearing workboots isn’t blue-collar cosplay. It’s buying boots that don’t suck. ➺ Read the last three paragraphs for a parable about where we’re at. ➺ Inside every bingewatcher there lives a truly great bobsledder. ➺ Please subscribe so I can rub it in my mom’s face.

The “LUSTFUL YEARNING SURVEY” is an attempt to understand what’s attractive to members of the Oat Milk Elite and what we’re willing to do about it. Full results will be shared with members and those that complete the survey.

Why casual skiing is on the decline.

Park City, December 2024. Ski patrollers making $21 an hour walk off the job at America's largest resort, where a mid-mountain lodge hamburger cost $25. Guests, some stuck on line after paying $328 for a one-day lift ticket, start to see the pay stubs patrollers have posted to their socials. Furious about what the stubs suggest about the mountain’s margins, they start to chant "Pay your employees!" – which is a lot more relatable than “Charge less!”

Lift ticket prices have risen 150-200% faster than inflation since the 1970s. Vail charged $9 for a day pass in 1972. That’s $68 in today's dollars. The actual price is five times that. Both prices and – odd as it may sound – ski runs, have gotten steeper.

In 1980, America had roughly 700 ski areas, most family-owned operations where the guy running the lift also fixed the snowcat. In 1992, Apollo Global Management acquired Vail Associates. In 2018, KSL Capital Partners and Henry Crown and Company (owners of Aspen) formed Alterra Mountain Company.

Today, Vail Resorts, which owns 42 mountains across four continents, and Alterra Mountain Company, which owns 15 mountains (including Aspen), control roughly half the market. They have completely overhauled how lift tickets are priced.

What private equity figured out is that the limit on a famous mountain’s revenue is congestion, not demand (long lines ruin the product). As such, the salient question is how to capture the most value from the fewest skiers. The best way to do this is by optimizing for the lifetime value of frequent skiers and the daily value of the not-so-frequent skiers clogging the blue runs.

In 2008, the reconstituted Vail Resorts launched the Epic Pass, which cost $579 – roughly the cost of seven single-day tickets – and provided season-long access to Vail, Beaver Creek, Breckenridge, Keystone, and Heavenly. This allowed Vail to lock in frequent skiers early, gain pre-season liquidity (in case of unseasonable actual liquidity), and push up the price of day-passes without risking the business3. The gamble paid off.

By 2023, Vail was selling 2.4 million passes at $1,051 a pop and bringing in roughly $900 million in pre-season revenue. Today, over 75% of visits to Vail properties come from passholders. Alterra copycat Ikon Pass costs $1,429 and puts up highly respectable numbers. And because the mountains aren’t congested and the marginal cost of an additional skier is essentially zero, operators can extract value from season passers one $35 hamburger at a time. Vail calls this "ancillary revenue." It now accounts for a large part of their mountain-segment income4.

These changes have been good (not great) for serious skiers, but have drastically driven up the price of going skiing for a week, which used to be an annual ritual for a broad swathe of the Upper Middle. Many Millennial parents who were fortunate enough to learn the pizza slice as kids aren’t getting their kids up a lift any time soon. If they want to spend five days on a mountain, they have to choose between a pretty bad deal on a season pass or a really bad deal on a bunch of day-passes. The result?

Casual skiing isn’t really a thing. In 2023, Aspen's first major terrain expansion since 1985 added 153 acres — and not a single beginner run among them. No long groomers. No friendly little glades. Nineteen double-black-diamond chutes and four expert trails.

What does a week out west actually cost a family of four? A single day at Vail approaches $1,500 once you factor in lift tickets, rentals, and lunch. A week, or five days on the mountain with slopeside lodging, lessons for the kids, and the occasional overpriced hamburger, runs closer to $13,000. That's before flights. Lodging has gotten particularly brutal as climate change limits the number of truly wintery locales; families are competing for fewer beds with reliable snow.

1995 | 2025 | Delta | |

Lodging | $1,050 | $3,000 | +$1,950 |

Lift tickets | $790 | $5,660 | +$4,870 |

Lessons | $420 | $1,200 | +$780 |

Rentals | $420 | $875 | +$455 |

Food | $788 | $2,000 | +$1,212 |

Flights | $1,680 | $2,400 | +$720 |

Hanna Horvath is the financial journalist and certified financial planner behind the (excellent) Your Brain on Money newsletter. When she’s not writing about money, she enjoys thinking about writing about money.

WIPED OUT

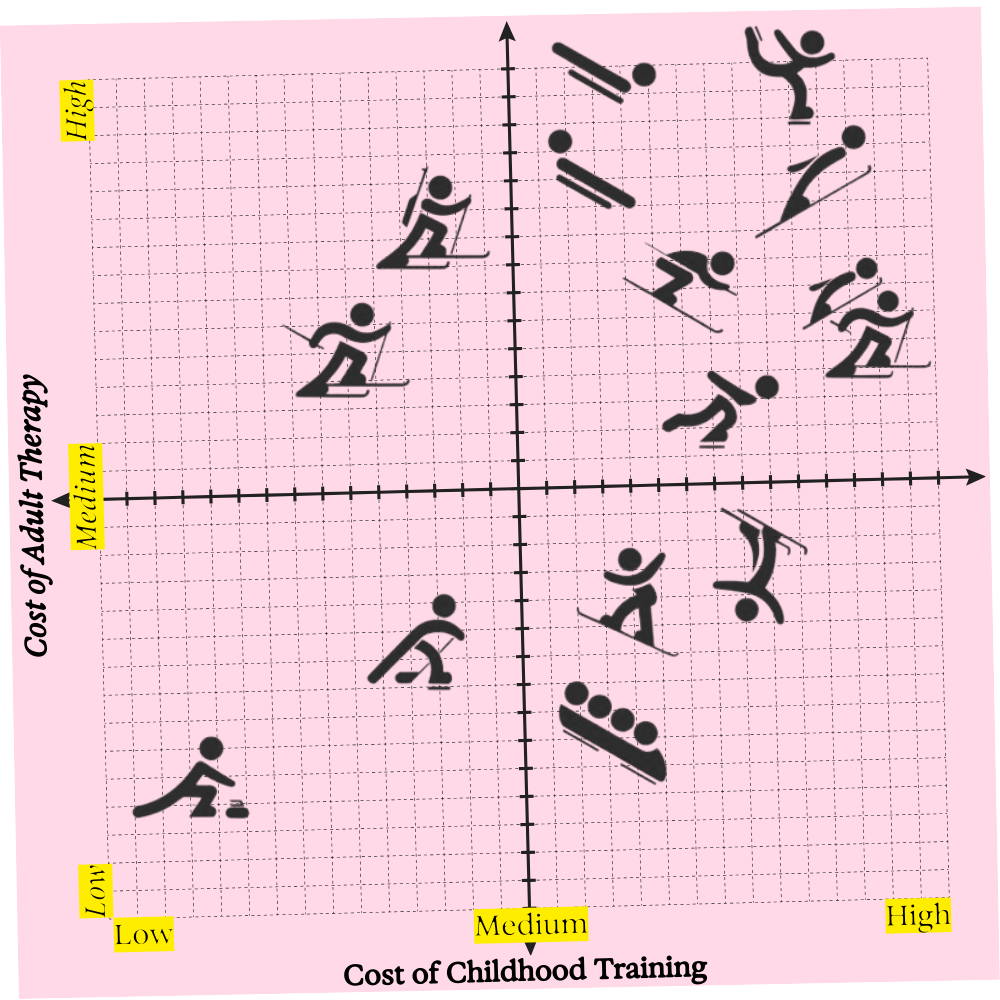

Strip away the overture and the Ralph Lauren outfits and the Winter Olympics are a simple: The coldest parents on Earth compete to see who can pressure their child into securing a one-off, six-figure fintech sponsorship before tearing their Achilles. A carnival of refrigerated carnage, the Games are dominated by the sort of inscrutable Caucasians (and cocky Asians) who encourage children to skate to Rachmaninoff despite knowing that – psychologically speaking – Tonya Harding probably represents the best possible outcome.

That said, not all winter sports damage the psyche equally. Snowboarders turn out fine if they're stoned, bobsledders turn out fine if they're concussed, and curlers turn out fine doing SAAS sales in suburban St. Paul. Ski jumpers, however, are a different story....

[1] This claim is really iffy. A lot of the benefits that accrue to people claiming disabilities like anxiety and ADHD – untimed tests, dismissal from group sessions – aren’t really beneficial to people who don’t have those conditions. As often happens, an institution has chosen a policy that is dumb but fair(ish) rather than smart but mean(ish). Reactionaries always hate that.

[2] For the record, I think Jason Alexander is exceptionally cool. He’s funny and a legit song and dance man who has crushed on Broadway. Also, for the record, what I think is cool is frequently not cool by the standards of the sorts of people who determine what is cool, most of whom are dweebs.

[3] This is sometimes called "yield management" or "dynamic pricing" – airlines pioneered it, AI has perfected it. The difference is that airlines sell perishable inventory (empty seats stay empty at departure), while ski resorts are managing a congestion problem (too many people ruins everyone's experience). And yet, the result is similar: Optimized extraction from committed customers, punitive pricing for those booking closer to the big day.

[4] Vail owns over 250 retail and rental locations. They own the shuttle from the airport. They own the hotel. They own the restaurant. The pass gets you in the door, but Vail keeps it’s hand in your pocket.